The long running issue from GROWING UP, rather than GROWING OUT in Development.

- By : James Bryson

- Category : Economy, Financials, Hotels, Housing, Human Interest, Infrastructure

Print, television, radio and digital media present at the end of each year a summary, among other things, of economic performance and expectations for the year that has just begun.

Authorities, business representatives, and independent analysts highlight how, from their perspective, the economy will develop in the future and whether this will allow for improvements in citizen well-being.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the main indicator of economic performance, is not what determines whether people see improvements in their quality of life. Other factors, which we will review, complement this assessment and determine whether GDP growth translates into increasing well-being for society.

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), in its year-end report, estimates that the economies that would have the best economic performance for 2026, from the conventional indicator, such as GDP, places Panama in an honorable fourth (4th) place with a growth of 3.7%, below Paraguay (4.5%), Costa Rica (3.9%) and Argentina (3.8%).

But, as I mentioned, GDP is not the indicator that can show whether its growth has real trickle-down effects on the population.

ECLAC shows how, despite growth levels, the Latin American region must face the three (3) development traps; the first being the low capacity to grow; the second, high and persistent inequality, low social mobility and weak social cohesion; and the third, low institutional capacity and ineffective governance.

Part of the international organization’s concern is that the persistent inequality in the wealth generated by each country results in the population moving from a peaceful or improving state of well-being to one where common or violent crime allows drug trafficking to position itself as the solution to obtaining more income, if what the GDP distributes does not reach everyone, thereby further eroding social cohesion.

We will focus our approach on two (2) of the six (6) factors that ECLAC identifies as key to evaluating inequality in the region, namely: low growth and a segmented labor market and large disparities in wages paid.

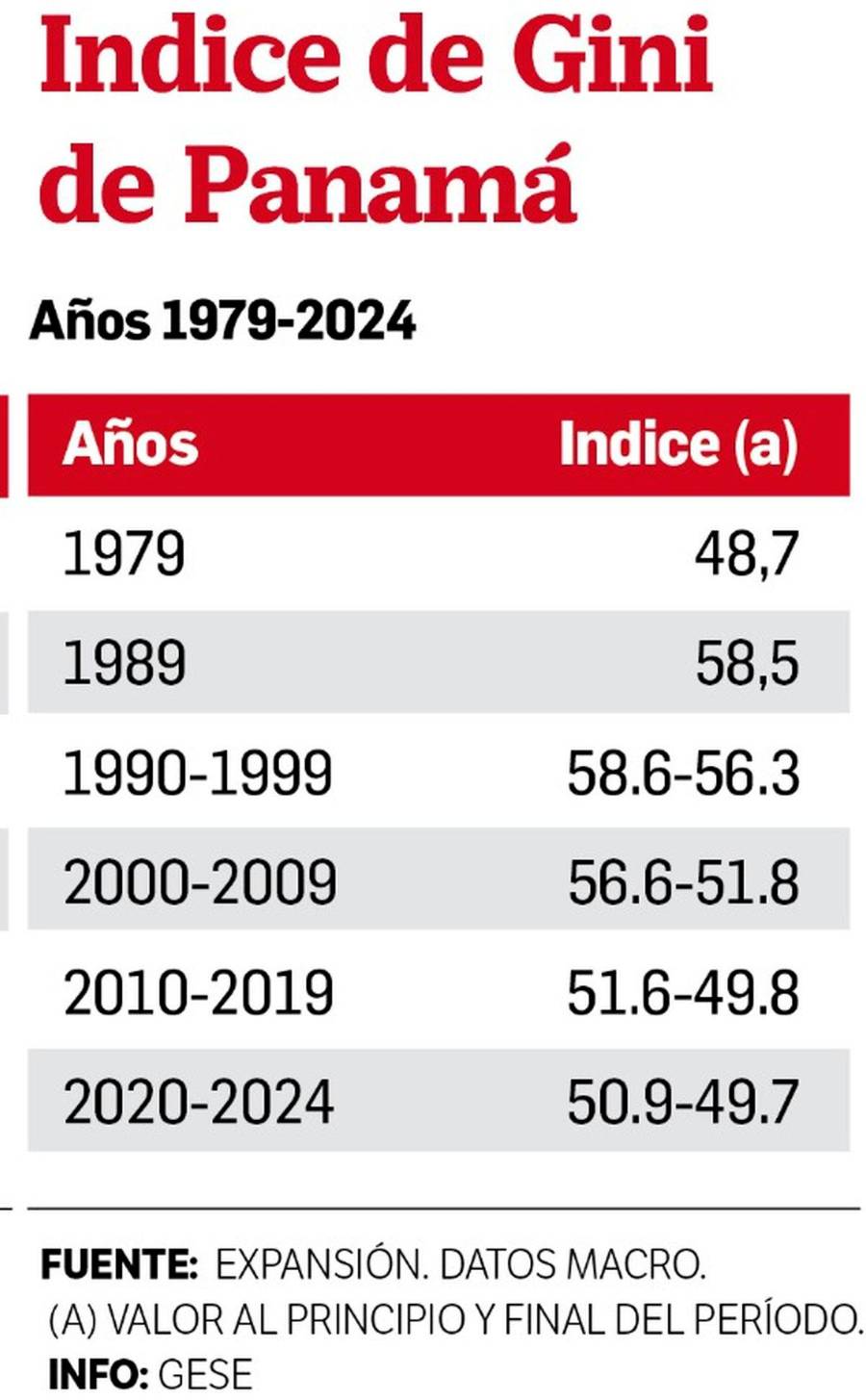

This coefficient, which ranges between 0 and 1, is a measure that tends to quantify, in a general way, the inequality in the distribution of income in a country.

When this indicator approaches 1, it shows that income is heavily concentrated in the wealthiest social strata, to the detriment of those with lower incomes. Conversely, as the values approach 0, they tend to indicate a more equitable distribution of income in society, leading to improvements in the population’s well-being.

Let’s look at some figures and compare the state of inequality between some countries and Panama.

Apparently, Panama has not shown the best results in some years of the last decade, and this must mean that economic growth, on the surface, keeps inequality levels around the average of the index, but with a tendency towards concentration after exceeding 50%.

Let’s now look at a compilation of the historical behavior of the Panamanian Gini Index and what interpretation we can give it.

This record regarding the Gini Index reviews the changes in income distribution in Panama, denoting a constant change from values below 50%, as reflected in 1979, and the increase in income distribution at the end of the 1980s, close to 60%.

From 1989 to 2019 it is clear that year after year the income distribution gradually decreased to reach the average Gini coefficient, but the values clearly maintain a high level of inequality, fluctuating between the 50% and 60% range.

Since the reversion of the Panama Canal, despite the increasing contributions of the canal’s operation to the national treasury and the modernization in all areas of our economy, it is clear how income distribution in Panama tends to concentrate among those who earn the most.

Although recent years show a trend below 50%, this period is heavily influenced by the pandemic years and could not be considered a change towards a real improvement in the quality of life of Panamanians.

Evaluating Latin American performance as a whole, according to data compiled by ECLAC, the three countries with the worst income distribution at the end of 2024 are Colombia, Panama and Brazil, in that order.

It seems contradictory that an economy as booming as Panama’s since 1990 to date, with the exception of the Covid-19 period, is the second most unequal in terms of the income a person can receive.

Like the Gini index, other indices, such as the Theil and Atkinson index, are often used to assess inequalities in income distribution.

While the Gini index encompasses all income, the other indices allow for the breakdown of the type of income received by the population or certain strata (deciles), emphasizing the amount of “transfers” that form part of total income, as measured by the Theil index, or when the analysis of income allows for its breakdown before or after the payment of taxes and basic benefits, as the Atkinson index does, but these will be evaluated soon, in light of the Horse and Sparrow Theory.

“Despite some improvements recorded in the last decade, income inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean remains structurally high. While the Gini index showed slight decreases in the last ten years, these do not reflect profound transformations, but rather small-scale variations influenced by the economic situation.” (Social Panorama, 2025. ECLAC).

The announcement by the authorities and national business community about future expectations based on planned investments, or that tax revenue will increase and lead to more investment and, consequently, more jobs, is of no use.

If that happens, perfect; however, there are other aspects to consider, and the figures we have examined should allow us to be realistic about the announcement of millions in investments if the rest of the problems are not addressed with focused public policies.

No Comments